#37 Making better decisions as an engineer

Understanding decision types for effective engineering

With the rise of AI slop across the internet—especially within engineering orgs—strong decision-making has become increasingly valuable skill for engineers.

Some make the mistake of having a project get blocked by a decision without exploring possible paths forward. Others delegate too many decisions, which can slow down overall progress. Vibe-coding is a form of delegating decisions to AI tools.

Decision-making is a skill in its own right: it requires practice and a framework to follow, particularly as you take on projects with growing impact. Engineers can still be good decision-makers even when projects fail for reasons outside their control. What matters is having the right mental model for evaluating decisions and weighing consequences against reversibility, which I’ll cover in the post below.

I’ll start by introducing Amazon’s decision-making culture by Jeff Bezos, then discuss the cost of decisions and their consequences, and finally share examples of how engineers can make better decisions.

First, let’s start with decision types.

Decision types

Bezos introduced the concept of “decision types” to encourage better and faster decision-making, which later became a core part of Amazon’s culture: Type 1 and Type 2 decisions. He wrote the following in a shareholder letter:

Some decisions are consequential and irreversible or nearly irreversible – one-way doors – and these decisions must be made methodically, carefully, slowly, with great deliberation and consultation. If you walk through and don’t like what you see on the other side, you can’t get back to where you were before. We can call these Type 1 decisions. But most decisions aren’t like that – they are changeable, reversible – they’re two-way doors. If you’ve made a suboptimal Type 2 decision, you don’t have to live with the consequences for that long. You can reopen the door and go back through. Type 2 decisions can and should be made quickly by high judgment individuals or small groups.

As organizations get larger, there seems to be a tendency to use the heavy-weight Type 1 decision-making process on most decisions, including many Type 2 decisions. The end result of this is slowness, unthoughtful risk aversion, failure to experiment sufficiently, and consequently diminished invention. We’ll have to figure out how to fight that tendency.

Type 1 Decisions (One-Way Doors)

Type 1 decisions are irreversible and have long-term consequences.

These are decisions that set the direction and strategy of a company, like entering a new market, launching a new product, or reorganising teams.

For engineers, these decisions should be made slowly and carefully, with analysis and forward thinking. For example:

Choosing a cloud provider

Defining public APIs

Designing your data and security model

Picking a primary programming language for the product

These are examples of decisions that require research, deep thinking, and discussion with impacted stakeholders (tech leads, managers, directors, and CTO).

A strong sign of leadership is the ability to identify Type 1 decisions, draft proposals, and discuss them with relevant stakeholders. These are decisions that will eventually be maintained by engineers, so it’s important to take time to explore alternative solutions and tradeoffs.

Type 2 Decisions (Two-Way Doors)

Type 2 decisions are reversible and have short-term consequences.

These are day-to-day operational decisions, like handling customer issues or implementing new product features. These decisions should generally be made by engineers directly and shouldn’t require a long chain of approvals. It’s valuable to communicate these decisions proactively, but don’t block yourself waiting on others (especially when the action is reversible). For example:

Configuring CI/CD pipelines

Adding feature flags

Trying a new frontend framework or changing ORMs

Refactoring a service

These are examples of daily decisions that can be made quickly, and if the outcome is inefficient, it’s not the end of the world. These are often reversible or disposable ideas that don’t create meaningful consequences for the company or its users.

As an engineer, you’re trusted for your technical contributions, which are usually a combination of making fast Type 2 decisions and carefully reviewing Type 1 decisions.

Junior engineers often get blocked here, sometimes due to lack of experience. That’s normal during onboarding/training. But it’s important to build this mental model when working on a busy team: senior engineers and tech leads won’t be available to review every Type 2 decision, especially when it’s reversible.

🌟 My advice: ask for input on high-level decisions (like a design proposal) and make Type 2 decisions yourself (e.g., implementation details).

Changes are always reversible in a pull request.

Decision costs

Decisions fall on a spectrum from reversible to irreversible. You can tell where a decision lies by asking how much it would cost to undo it. The higher the cost, the more irreversible the decision.

As you progress in your career, there will be all kinds of decisions you need to make. Understanding the impact and cost of each decision is important and will make you stand out as an influential leader.

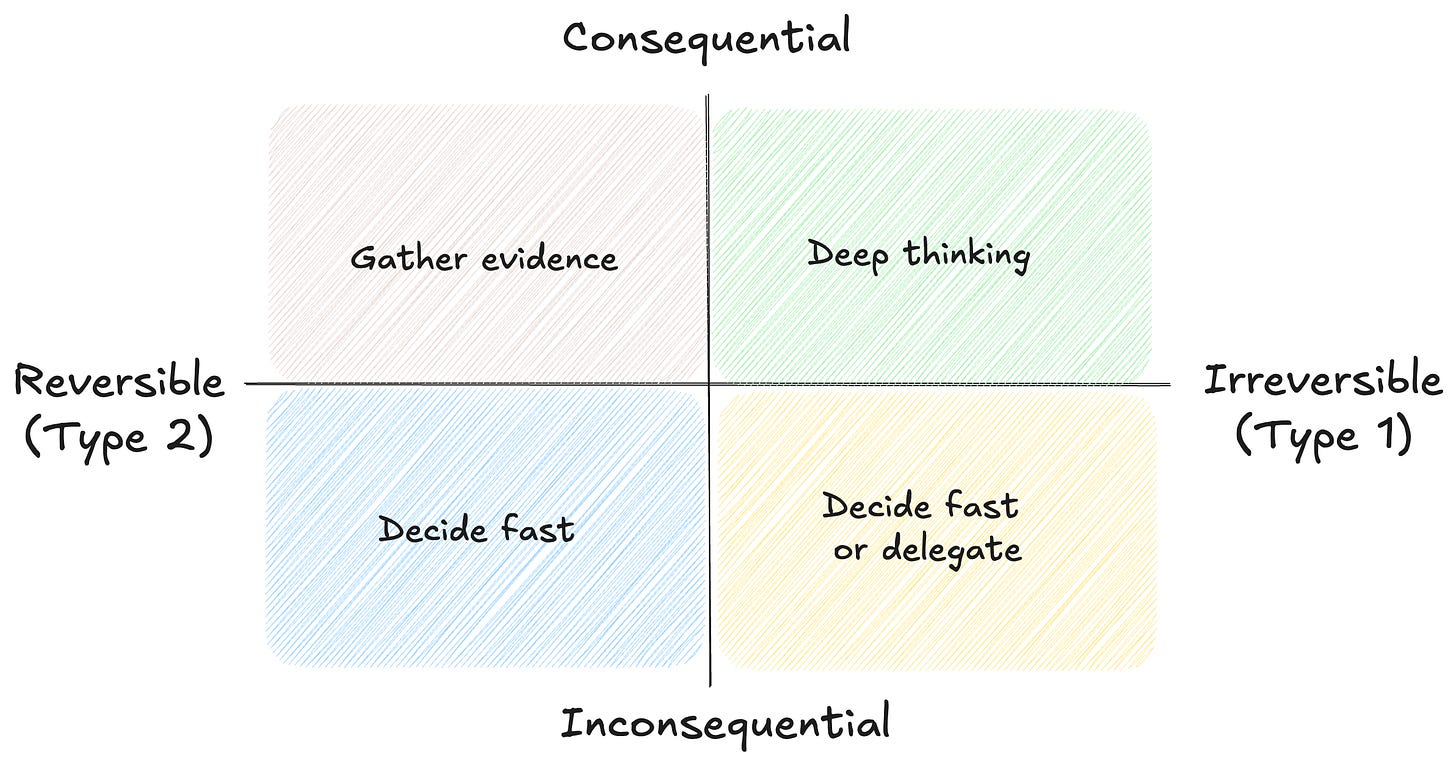

The following diagram frames decisions along two axes:

Reversibility (x-axis)

Consequence (y-axis)

To build the right mental model, this diagram suggests the action based on two factors: reversibility and consequence. The top two quadrants represent high consequence to your team and the business, while the bottom two quadrants represent minimal consequence. The top-right quadrant represents “technical excellence”: high-consequence, irreversible decisions that require deep expertise and long-term thinking. The top-left represents “prototyping”. It’s for building a hypothesis and then running experiments to validate or nullify it, and explaining the results to other engineers. The bottom-left quadrant is for quick decisions on small items. Engineers don’t have to spend too much time on this, especially if it’s easy to undo. The bottom-right quadrant can also be delegated or decided quickly. It might be useful to communicate those kinds of decisions with your teammates, but it certainly doesn’t require hours of meetings back-and-forth.

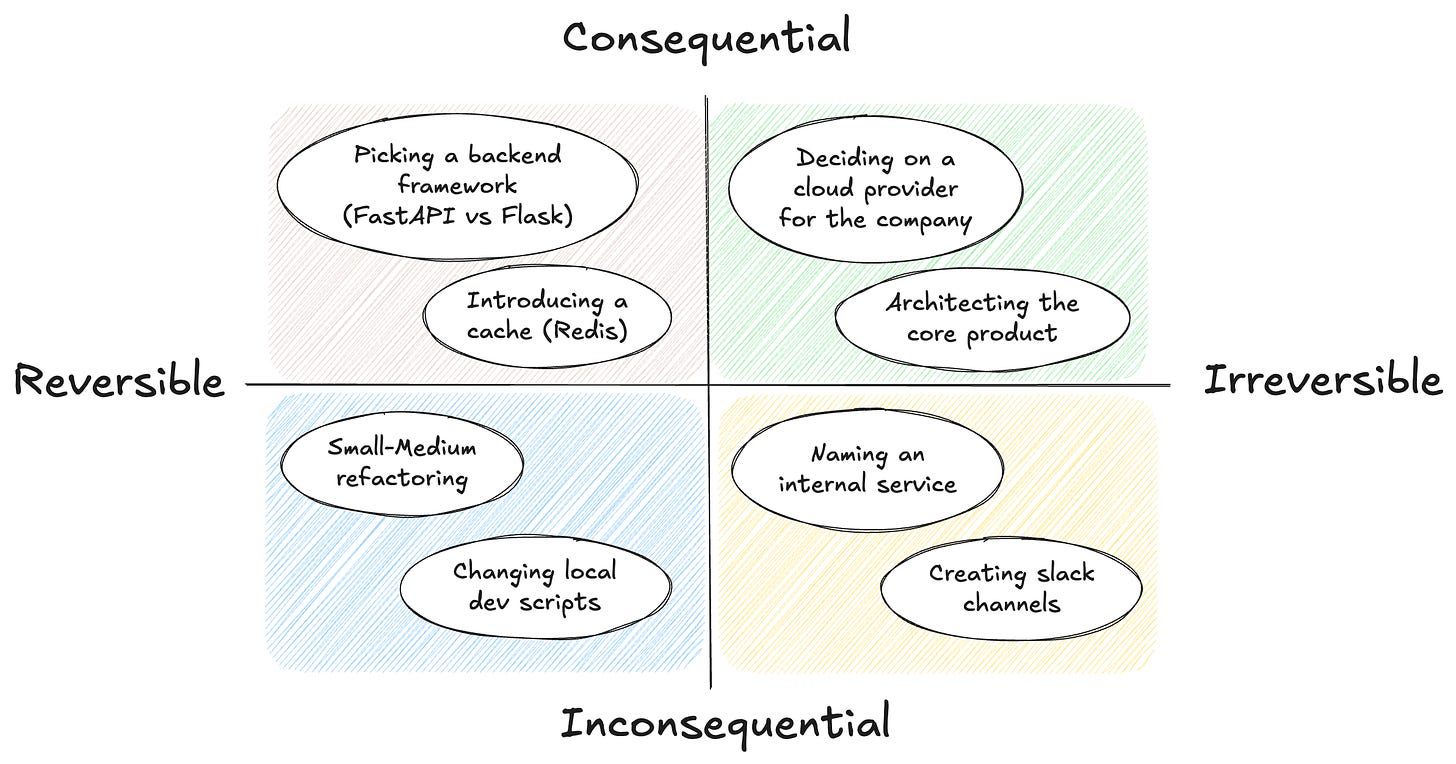

Below are example decisions you might face as a software engineer.

In startups, you’ll often be exposed more to the top-right quadrant: consequential and irreversible decisions. In larger companies, you’ll see more of the top-left quadrant: consequential but reversible decisions. However, you’ll face all sorts of decisions throughout your career regardless of your chosen environment.

Junior and mid-level engineers typically start in the bottom quadrants and level up to the top quadrants over time. For the top quadrants, senior engineers are typically needed for the top-left, while staff/principal engineers are required for the top-right.

🌟 A useful way to think about career growth is the consequence of the decisions you make. If your decisions can meaningfully impact customers or the business—and succeed—you’re trusted as a strong engineer.

🌟 If you’re mostly making inconsequential decisions, your work likely has limited impact. Reorient toward business outcomes and seek opportunities to make higher-consequence decisions with your manager.

Conclusion

I’d highly recommend building mental models around decision types and consequences. Whether you’re an IC or a tech lead, knowing where to spend time and energy in decision-making is critically important to the business. Teaching others how to make better decisions also provides a great return on investment. Knowing when to delegate, prototype, or bring together a group of engineers for an important technical decision is a skill that requires practice and repetition.

My suggestion moving forward:

Reversible & consequential: Prototype and get buy-in before executing.

Irreversible & consequential: Research, think deeply about the options, and discuss with relevant stakeholders.

Irreversible & inconsequential: Decide quickly or delegate. Don’t waste time.

Reversible & inconsequential: Decide quickly and undo if needed. Don’t waste time.

My final takeaway is this:

Your career grows in proportion to the consequences of the decisions you’re trusted to make.

If you enjoyed reading the newsletter, consider subscribing and sharing it with a friend.